We learn the rope of life by untying its knots.

~ Jean Toomer

Looking back on it after so many years, it’s obvious to me that my father hadn’t tied a fly onto a leader in a very long time.

“So, after you go through the eye of the fly,” he instructed, “you twist it around five times.” He fumbled here, trying to hold the knot far enough away to keep it in focus.

“Then you take the end and go back through the little hole before you lick it and pull it tight.”

“Wow!” I said. “What d’ya call it?”

He looked puzzled for a moment. “A fisherman’s knot,” he said finally with a smile.

“Are there more?”

“Naw, kid… this is the only one you’ll ever need.”

I fished for many magical years with this single knot and a few variations of it. When I needed to join two lengths of leader, for example, I simply tied opposing fisherman’s knots and called it a blood knot. It wasn’t until my first year guiding in Alaska that I watched one of my fishermen tie a blood knot properly, grasped the concept, and began to tie it correctly myself.

Sometime afterward one of my clients informed me that my “fisherman’s knot” was really just a quaint name for a clinch knot. Furthermore, I was informed, the improved clinch knot was far better. He even quoted me percentages. “Your old clinch knot is only a 75 percent knot at best — the improved clinch is at least an 85 percent knot.”

Once knots began to be described by the percentage of the line’s breaking strength, the race was on, and different manufacturers and tackle companies began to claim trademarks on knots that were designed for them in contests they held. Now we have the Trilene Knot and The Orvis Knot, etc.

It seems to me that we’ve gone a bit knot-crazy. It used to be that the few knots a fly fisher needed to know barely filled a chapter in one of the few old fly fishing guides. Now there are more than a dozen books dedicated solely to knots and three by one writer! Further, there’s a perception among anglers that the more knots you know, the better the fisherman you are; that a certain amount of status can be attained by knowing and using a knot that no one else has heard of yet.

I’ve overheard some fly fishermen speak in hushed tones about knots — like others do about their rare bamboo fly rods, custom tied flies or distant and exotic rivers. I won’t be surprised if one day I’m asked to look at a shadow box in someone’s den that contains a collection of clipped knots — The Duncan Loop, Tied by Lefty Kreh, or A Riffle-Hitch, Tied by Lee Wulff.

Anglers used to judge the success of their day by the number and size of fish they caught. When I was a kid, we’d simply say, “We caught a dozen trout, and four of them were over 16 inches.”

Somewhere along the way, technique became important: “We caught a dozen trout on dry flies.” Then the size of the fly became significant (the smaller the better). “We caught them all on size 24 Compara-duns.”

Then, the length and diameter of the leader came into play: “They wouldn’t touch a fly on anything shorter than a 14- foot leader with three feet of 7X tippet.”

These days some anglers talk about what knots they’ve had to resort to in order to fool a wary fish: “Why the big guy refused every fly I threw at him until I tied it on with an inverted, non-slip mono-loop.”

There must be a lot of pressure on today’s fly fishing writers to beef up their books with more and more knots, lest they be considered naive. When I was asked by Tom Rosenbauer, to illustrate the re-issue of his classic Orvis Fly-Fishing Guide, I decided to put my knot prejudices aside and try to learn everything that I could about knots. My goal was to illustrate them so that people (like me) who have trouble tying them could easily catch on to the instructions.

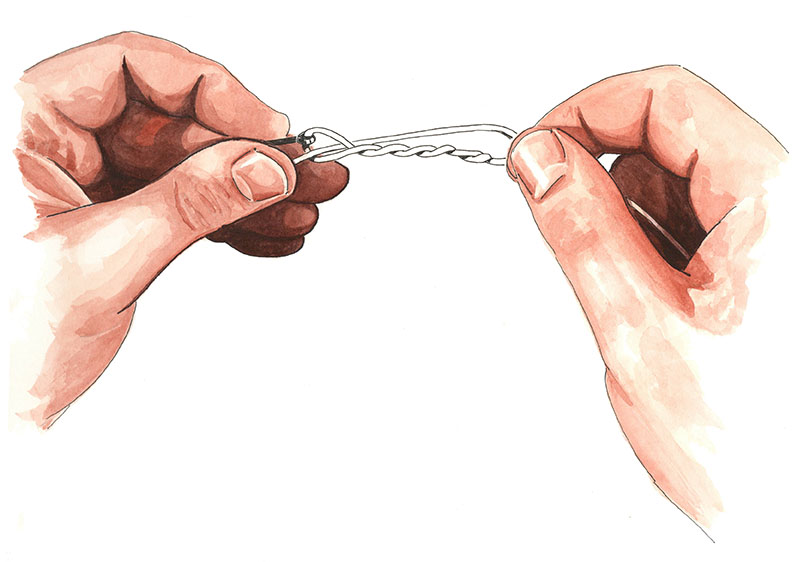

I asked an old friend to serve as a “hand model” and photographed him in each stage of the tying processes of each knot. I learned a lot that day as my friend and I argued about how certain knots are tied. I had assumed that there was only one way to correctly tie a knot — in fact there are sometimes, many.

First, one needs to consider if the knot begins with the end of the line passing through the eye in a downward or upward direction (I thought this was arbitrary). Then, if wraps are done in a clock-wise or counter clock-wise manner (I believed that it really didn’t matter, as long as one was consistent throughout the process). On top of everything else, there is the matter of whether the tier is left or right-handed. I can assure you, left-handed people like myself, look at the world differently than the rest of you right-handers.

I became haunted by the challenge of how to tie knots correctly. I researched knots on the Internet and I found entire websites and blogs devoted to picking them apart, literally. One website was even animated. I purchased every book about knots I could find, and then began collecting older volumes to see if there was some sort of evolution in a knot’s life. I discovered there were sometimes as many as three different “correct” instructions for tying a single knot —sometimes by the same author and illustrator!

I was still in a state of recovery from my book project when I received a phone call from a publisher who wanted to know if I’d write and illustrate my own book of fishing knots. My skin crawled and I started to twitch uncontrollably at the mere thought of it.

Later that summer, my wife and I took our (then) three-year-old daughter fishing for the first time. As we floated around in the lily pads of a local lake, I strung up a cane pole for her.

“This is how you tie on the hook,” I explained, fumbling for my reading glasses. “After going through the eye of the hook, you twist the end around the line five times. Then you take the end and go back through the little hole. Then you lick it, and pull it tight.”

“What’s the name of that knot?” Tommy asked.

I didn’t hesitate. “It’s called a fisherman’s knot.” I said. “It’s all you need to know.”