“Ach der lieber!”

– Grandpa, Leo Schoenherr

Another childhood summer neared its languid end, and Labor Day was marked by the annual family reunion and the start of dove season. That the two fell on the same day was no accident, and to insure a memorable shoot, my Uncle Gene always planted a sunflower field.

I’d received my first shotgun the Christmas before, and even though I’d already hunted with my father several times, I was told on the eve of the big day that I’d have to wait a year or two before I could shoot in the family hunt.

“Son, a dove field can be a mighty dangerous place,” my father explained. “There’s lots of action, fast shooting, and plenty of other folks around.

“I know that we’ve hunted together, and that you’ve proven yourself to be a safe partner, but I think it’s best to wait a few years.”

The look of disappointment on my face stopped him.

“I’d tell you that you can bring your gun, and leave it unloaded, but I don’t think it would be the same now that you’ve hunted.”

Of course my father was right, but it didn’t make the bitter pill any easier to swallow. I also knew that once he’d made a decision, he rarely changed his mind.

“I’ll tell you what,” he continued with a smile. “Why don’t you join me, and we’ll share the model 12.”

“Wow! Really!”

“Once things have settled down a bit,” he said with obvious relief, “we’ll get you some practice.”

I went to sleep that night wondering what it would take to shoot a dove out of the busy sky over a sunflower field. Now, it was true that I had shot several doves, but these had been birds flushed from the edges of grain fields. I’d never taken a poke at any that were sailing downwind with several ounces of lead to hurry them along.

The following morning crawled along at an agonizing pace. It took forever to load the station wagon with the coolers of fried chicken, salads, slaws, and cakes. We stopped by the icehouse on the way out of town to pick up some blocks for the tubs of soda, and my father let me relieve my pent-up frustration by chipping them down to size with an ice pick.

The drive seemed to take forever, and the stop in Lively Grove, at Waller’s General Store for fresh bread didn’t help. Things were in full swing when we finally made it to Benny and Angela’s farm. Relatives waved and hollered in greeting as we drove down the field road and parked in the shaded wood lot.

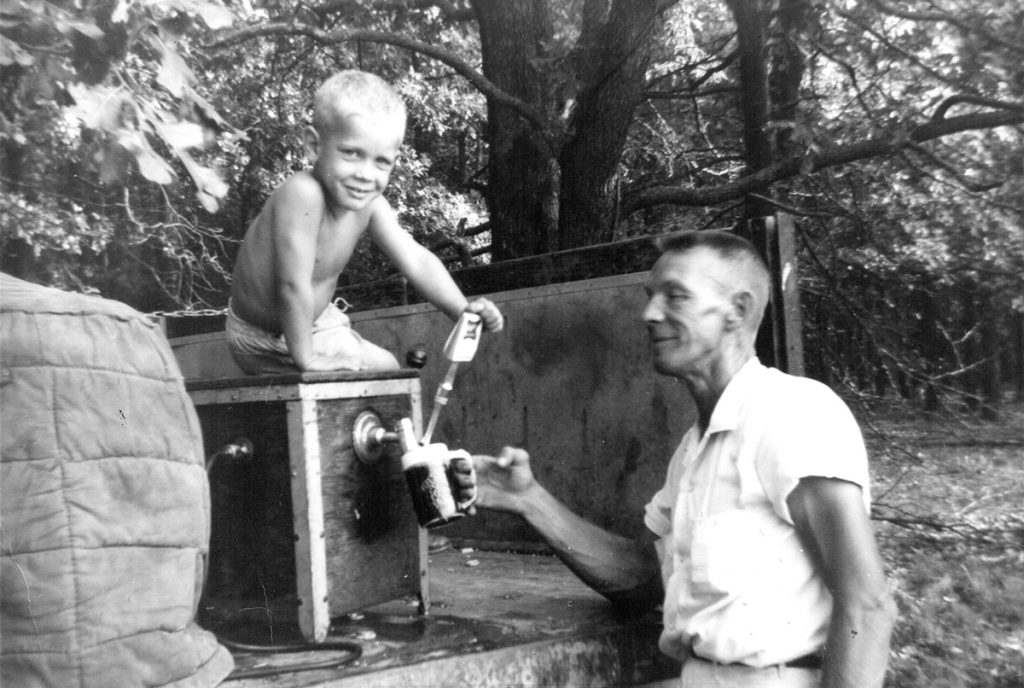

I was immediately transfixed by the pageantry of a good old-fashioned family reunion. The sawhorse-and-plank tables bent under the weight of food, and there was a bed of coals on which to grill pork steaks and homemade sausages. Three of the younger cousins took turns at the hand-crank on an ice cream freezer. On top of the pile of quilts that blanketed the freezer, and struggling to maintain his precarious perch, sat my grandfather, Leo.

It was the only day of the year that I was allowed to drink all the soda I wanted, and my mouth watered at the sight of a huge washtub filled with the small thick bottles of grape, strawberry, orange, root beer, cream soda. All the flavors were present, and covered in a mountain of shaved ice. Two bottle openers were tied to the tub’s handles with bailing twine.

The ringing of multiple horseshoe pits provided a background to the hum of the place, and the alternating moans of losers and the laughter of the winners was in perfect concert with the clanging of the shoes. My cousins played their accordions, and a cork ball game was under way.

“Hey Tippy,” an uncle grinned, “Marcela says you just got a brand new TV set.”

My great-uncle, Tip, looked up sheepishly, and his wife Marcela replied.

“Ach… don’t you know, Richie, he shot da TV last week ven he was cleaning his gun for da dove hunt. Mein gott im himmel, vot a mess. Poor Walter Cronkite!”

Everyone howled with laughter as Uncle Tip raised a finger in protest, thought better of it, and resigned himself to tapping a second barrel of beer. On a table next to the beer were dozens of tin beer-buckets. They were seemingly identical, but each was intimately known.

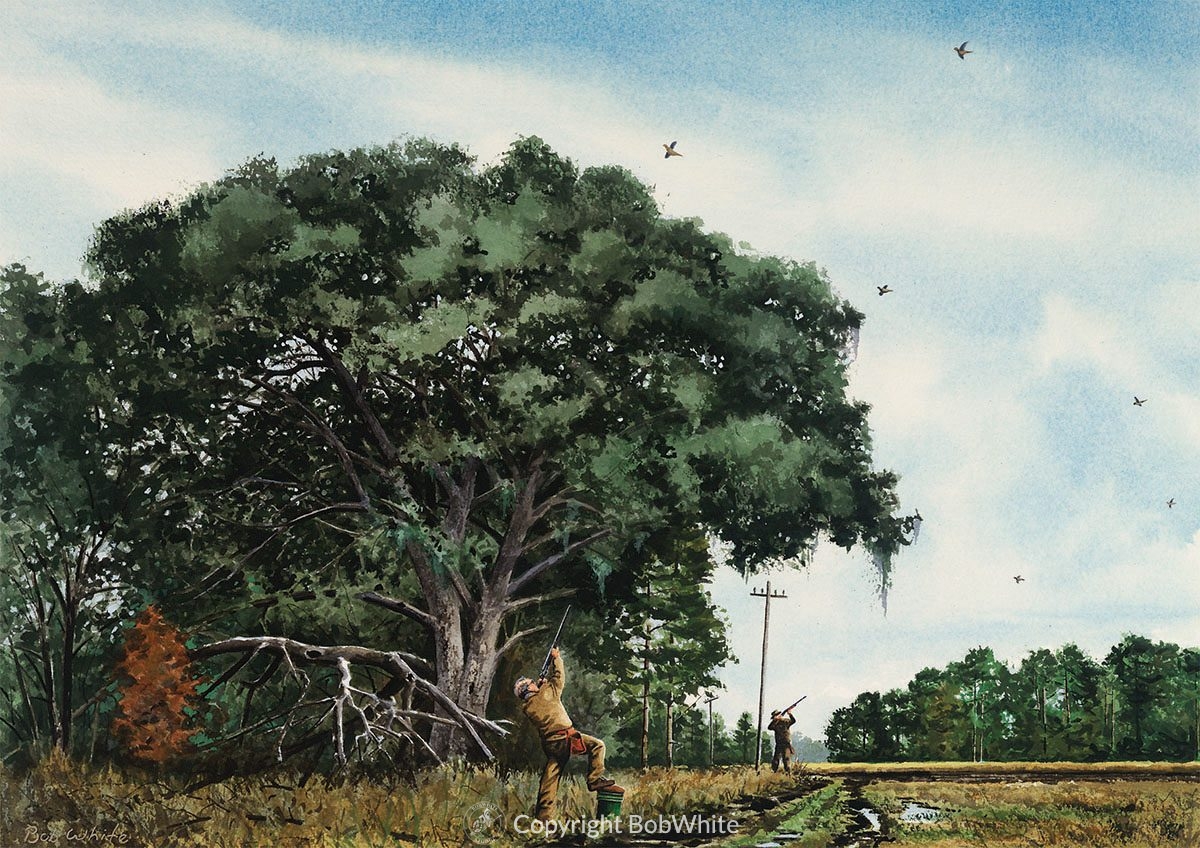

I was having such a good time that my father had to remind me that the shoot was about to begin. The field where we’d hunt was a half-mile distant, and the sunflowers had been knocked down a week before. Conveniently, the wood lot where we held the reunion was the largest dove roost in the area, and all the birds, driven out by our presence, were in the field or on the power lines that bordered it. Occasionally a dozen or so would fly back to their roost only to be frightened off and loaf back to the field.

All of the men and older boys climbed onto a hay wagon, the center of which was piled high with crates of shells and cased shotguns. We sat around the edge with dangled legs as Benny’s tractor pulled us down the lane. We were dropped us off as he circled the field, and when finished, he headed back to the grove, as he was in charge of the grill.

Doves buzzed around the place like bees whose hive had been knocked over, and the shots began before Benny got back to the picnic. He’d return for us later, when the shooting stopped and the slow-cooking sausages were done.

My father found us a spot on a fencerow, under an Osage orange tree, and directed me not to retrieve any birds from the field until after the hunt. No sooner had he spoke, than two doves flew past us, going away. The 16-gauge model 12 barked twice and the pair crashed to the ground. My father then crouched, gun held low, waiting until an incoming bird was almost upon us. When he stood the bird flared in a towering climb, but before he pulled the trigger it disappeared in an explosion of feathers.

“Haw haw!” shouted an uncle. “Wiped your eye on that one!”

“Nice shooting, Virgil,” my father conceded, though not too convincingly.

Virgil then threw three shots at a crossing pair but only managed to wingtip one. My father saw his chance and crushed them both with two quick shots.

“Virgil, you let me know if you need any more help!” he said in a voice loud enough for all to hear.

“Yeah, yeah,” Virgil mumbled.

The shooting was riotous. I was so intimidated by the speed of the birds, and in such awe of the shots being made, that I didn’t press the issue of my shooting. My father finally emptied his gun and handed it to me.

“Just load one shell at a time,” he said. “Then, you won’t have to worry about the second shot. I’ve seen you shoot… you’ll do fine. Don’t think about it,” he coached. “Just shoot the bird.”

I dropped one of the purple, waxed paper shells into the receiver and moved the forearm forward to chamber it.

“Now then; you’re a lefty, and this safety is all wrong for you. Wrap your finger around the trigger guard and push it off as you bring the gun up,” he coached. “That’s it… like that.

“On your left coming in low,” he whispered.

I’d never shot at a bird that I could watch from any great distance. I raised the gun to my shoulder while it was still out of range, clicked off the safety, and tried to follow its flight with the barrel. By the time I shot, I was waving it around like a yardstick-wielding nun.

“We’ll need to work on that,” he said, handing me another shell. “Keep your gun down until the moment you’re ready to shoot. Just watch the bird, and blot out every thing else. Ready?”

“Yup.”

“Good, from the left again.”

Half a dozen birds were strung out in line, crossing downwind. I watched the lead bird and waited… and waited… and finally threw the gun up and fired. A solid hit! The last bird in the line bounced in the field.

“Nice shot!” my father said, kindly slapping me on the back.

It was only then that I realized everyone else had stopped to watch. They were still cheering and whistling when we heard the tractor cough to life.

Benny arrived with a cooler that held several dozen iced bottles of beer and one strawberry soda. It took us a while to collect all of the doves, and they were piled into the now empty cooler. Shots were relived and bragged about on the short ride back, and everyone congratulated me again.

My uncle Richie smiled. “Is this your first dove hunt?”

“Yes sir.”

“Well now,” he said scratching his hairless head in mock thought, “what was it I heard about, fellas? You know, about first-timers?”

“He gits to pick the birds!” They shouted.

When we arrived back at the grove everyone was on their hands and knees, searching in the grass and sifting through the leaf litter.

“Vots go’n on here?” Asked Benny as he turned off the tractor and jumped down ahead of us.

“Benny! Careful ver you step!” Angela cried out and waved him back.

“Vot da hell?”

“Ach… Leo’s gone and lost his glass eye again!”

“He vot? Now, how’d he do dat?”

“Vell, he was playing tricks on the little ones, you know, where we slaps himself in the back of the head, and it pops out. Only he didn’t catch it.”

“It’s hard to catch ven you only have von eye,” offered Leo. He looked like a pirate, with a handkerchief tied around his head.

“Mien gott” mumbled Benny.

“Ahhhhrg!” Screamed one of the little girls as she pointed at the washtub of iced soda. “Mommy! Mommy! Mommy!” she cried.

“I think we’ve found Leo’s eye,” my father said, and we all crowded around the first washtub any of us had ever seen that could stare back.

Late that night we drove home listening to Harry Caray call the Cardinals game. After my mother and sisters had nodded off to sleep, my father looked over his shoulder at me and softly asked, “That bird you hit… was it the one you shot at?”

Then, he smiled to himself, already knowing the answer.

—

Post Script: I still have Leo’s beer bucket.