There is nothing like good food, good beer, and a bad girl.

~ Fortune cookie

I stood next to the truck, and stared at the rolling hills of wheat stubble. A hard frost lingered in the long shadows cast by the low morning sun, and as the day advanced, the bejeweled fields seemed to march away from the dawn, glistening for a few brief moments in their glory before the ice melted.

My friends intended to hunt deer later in the season, and the next few days were designed to be a scouting trip. There were several maps spread across the hood of the truck, held down by gloved hands and marked with grease crayons.

My mind had drifted away on the morning breeze, and the conversation between the owner of the ranch and his son seemed distant and unimportant, until the boy began to argue with his father. A hundred yards away a covey of sharptails flew past, their staccato wing beats and glides marking them as the prairie grouse I’d seen at a distance, but had never held in my hand. “Sharpies!” I said, interrupting the quarrel. I pointed, “They’re flying into the wheat.”

“Prairie-carp,” the kid mumbled. “You can have ’em.”

My friends and the kid turned back to the map, but the old man’s eyes, as blue as the sky they reflected, stayed on the birds. Their wings flashed in the low sun as they turned and settled in the stubble to feed. There was a smile in those eyes when he walked over to me. “That’s a nice bunch of birds,” he said.

“I’ve never shot a sharptail,” I responded. “Do you mind if I walk them up?”

“I’d join you if I could,” he answered, turning to look at the hills behind us, “but I’ve got beef to move before it snows. Are you sure that you wouldn’t rather hunt pheasants? That’s what the boy likes; drives ‘m crazy.”

“I’ve shot lots of pheasants,” I replied. “I’d rather hunt sharptails.

“Good,” he said. “Let the boy have his ditch-parrots.”

The kid climbed into the truck with my friends, and I fell in with the old man. Together, we bounced across the fields in his ranch truck. There was a suspicious hole in the floor, and he noticed me looking at it. “The boy likes to pot-shoot from the truck,” he said. “I’m glad I wasn’t along that day.”

He showed me around the ranch his grandfather had settled, and in the process told me all about prairie grouse. As I listened, it became clear that it would be extremely difficult to hunt these birds without a dog. “I’d let you use my old setter,” he said. “But Mac’s shoulders have plumb given out. The doc says I should put him down, but I just don’t have the heart for it.”

I’d walk them up on my own.

Eventually, we found ourselves back at the ranch house, where I met the old Gordon setter and had coffee with his daughter. “Kelly can give you a ride out past the alfalfa fields, and save you some time,” he suggested. “However you hunt them, come evening, walk the east-facing slopes, they’ll go there to roost.”

Kelly drove me out to the wheat fields. There was endless cover to hunt, but my plan was simple; I’d walk with the sun at my back until mid-day, eat my lunch while it passed overhead, and return with it behind me.

“Don’t be late for supper,” Kelly called as she headed back to the ranch.

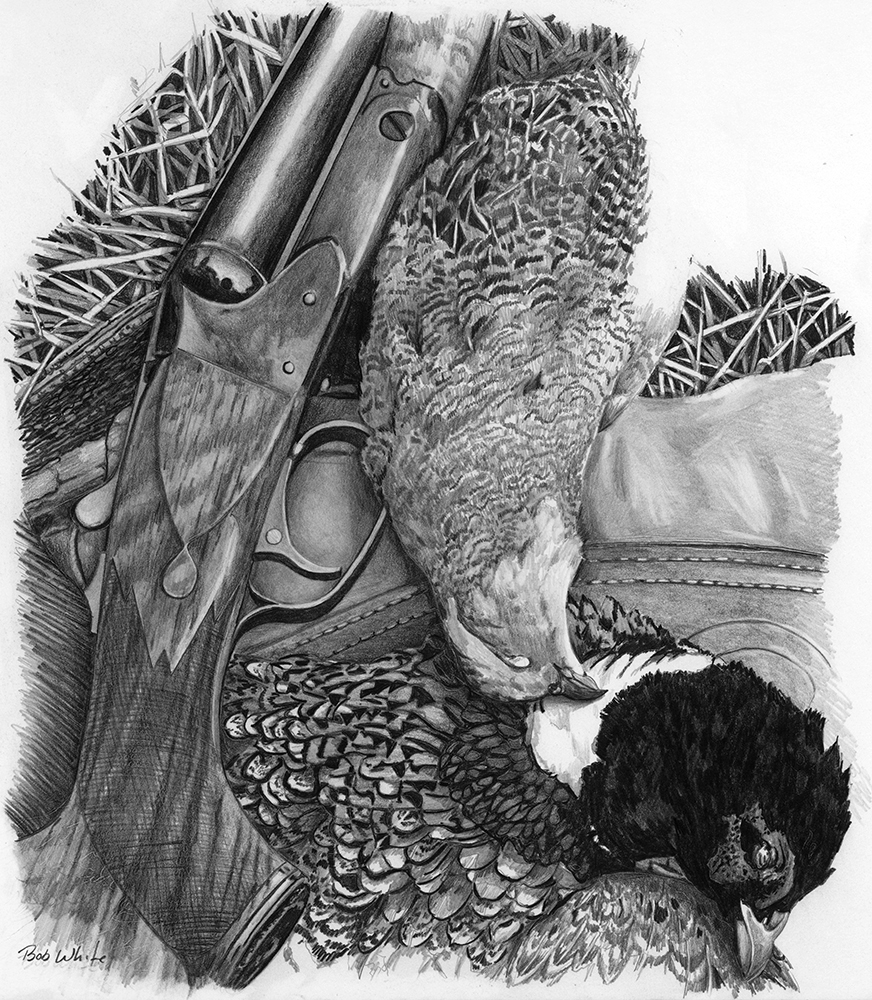

It felt good to start. I slipped shells into the double gun and began my hunt between the stubble and a brushy draw, dropping down into it whenever it broadened enough to look birdy.

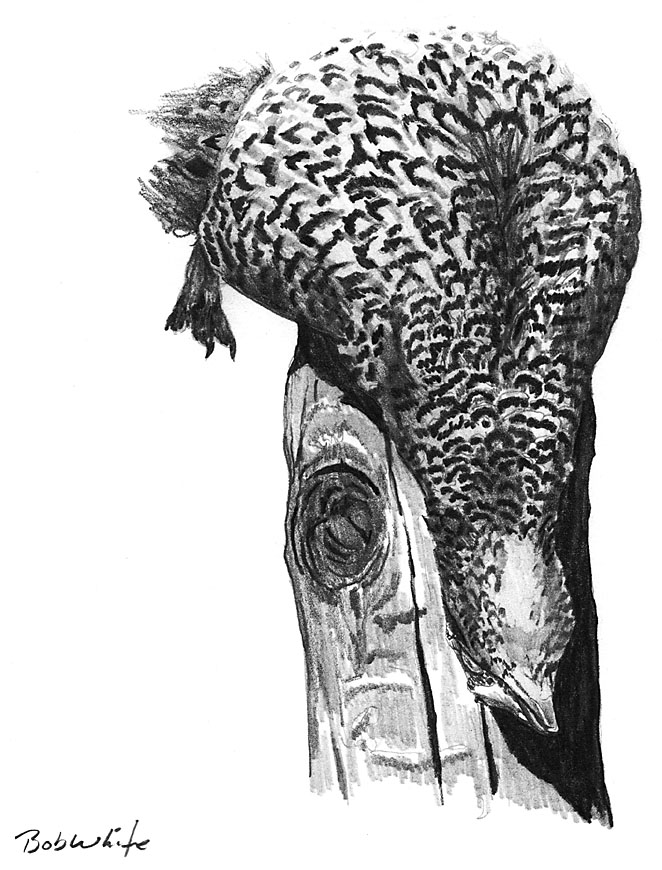

As I pushed my way through some tangled brush to get to an opening of sparse grass, a hen pheasant flushed. I was so keyed to see sharptails that I almost shot. The cackling of a second bird, as it towered into the sky saved the first, and I dropped the rooster. It’s weight felt right in my vest.

At mid-day I found myself in a wide draw, and preferring to look at the horizon and listen to the wind while I ate my lunch, I began to climb. As I stepped out of the high grass onto wheat stubble, a covey of Huns flushed off to my right, chattering as they made for the safety of the open field.

At mid-day I found myself in a wide draw, and preferring to look at the horizon and listen to the wind while I ate my lunch, I began to climb. As I stepped out of the high grass onto wheat stubble, a covey of Huns flushed off to my right, chattering as they made for the safety of the open field.

In my surprise, I missed with the right barrel, and the left one barked without me knowing that I’d pulled the trigger. My target continued on its way, seemingly unscathed. But, the bird began to slow, and then towered straight up for what seemed like a hundred feet. At the apex of its climb it flipped on its back and pin-wheeled, stiff-winged, in a slow spiral to the ground.

The little partridge made a perfect still life lying in the stubble where it’d fallen; the composition was natural, the colors rich and subtle. When I picked it up to examine it, I found that a single pellet had pierced its head.

I was ready for lunch, and sat down in a pile of straw next to the little bird. As an afterthought, I added the pheasant to the still life, and admired them both.

My lunch had been thoughtfully packed, and included pretzels, hard cheese, a tin of kippered herring, a big dill pickle, a bottle of hoppy Czech beer, and a tart green apple for dessert.

Just as the ingredients had been carefully selected, they would also be eaten in a thoughtful manner. I didn’t want to run out of any one item before they were all finished together. Lunch was concluded with a foamy mouthful of Pilsner. It was just enough; not so much that I didn’t want another swallow. It’s nice to finish a beer wanting a bit more.

There was a tuft of feather and dried blood on the blade of my Swiss knife from the last bird that I’d cleaned, and I scraped it away with my thumbnail before quartering the apple. As I savored its tart perfection, I wiggled into the pile of straw, and watched the high clouds pass. I may have fallen asleep. It seemed cooler when I finally sat up, stretched, and wondered about the rest of my day.

The sun had passed over me on its way toward evening, and it was time to hunt back to the house. As dusk came on, I remembered Kelly’s request not to be late, and decided to hunt back in a direct line. I was disappointed not to have seen a prairie grouse, but the weight of my vest was satisfying enough. I was happy with the day.

The shortest route back to the house took me across an enormous field of short grass, and as I crested the rise, a sharptail flushed at my feet. I missed with both barrels and watched my prize fly away, cackling with sarcastic laughter. It disappeared into a distant shallow bowl.

There was nothing else to do but follow, and as I walked into the depression where it had landed, it flushed a second time.

I missed again, and watched as it flew into the middle of an alfalfa field. I walked directly to where it landed, and was surprised that it held and flushed a third time. Mercifully, it didn’t have much energy left and I hit it with my second barrel.

I was in high spirits when I finally climbed the stairs to the porch and laid the three birds in front of the old setter. His eyes brightened, and it made me feel good to see his tail wag. The smell of dinner wafted from the kitchen, and my day seemed complete.

“There’s a mess of big ducks on the stock tank,” Kelly said from the kitchen door, “and Daddy loves roast duck. Do you think you can shoot him one?”

“Let’s get a bunch of them,” I said, “I have a second gun. Can you be my loader?” Kelly giggled, and we were off.

“This is great,” I said. “The only thing I haven’t shot today is a bunch of ducks.”

“We just need one,” she said.

“Oh, no problem,” I insisted.

We crept up to the earthen berm that held back the tank and slowly peeked over. There were a hundred northern mallards and pintails crowded onto the small pond. I could have easily killed a dozen of them on the water.

“Here’s what we’ll do,” I whispered importantly, as I loaded the two guns and handed one to her. “We’ll both stand up to flush them, and after I empty the first gun, you hand me the second.”

Perhaps, because they felt a safety in their number, the ducks didn’t flush when we stood, and there was an un-nerving delay before they erupted. I don’t recall much about the next few seconds. I don’t remember picking a single bird, as I’d been taught as a boy. I don’t remember the first two shots, or taking the second gun from Kelly and emptying it too. I don’t remember watching any ducks fall to the water.

What I do remember is the sick feeling of disbelief as all of those ducks flew away, and that Kelly’s laughter sounded a lot like a sharptail’s cackle as she walked back to the house.

In the end, I’d have to add a little crow to the day’s menu.