Someone once described me as a collector, and I suppose they’re right.

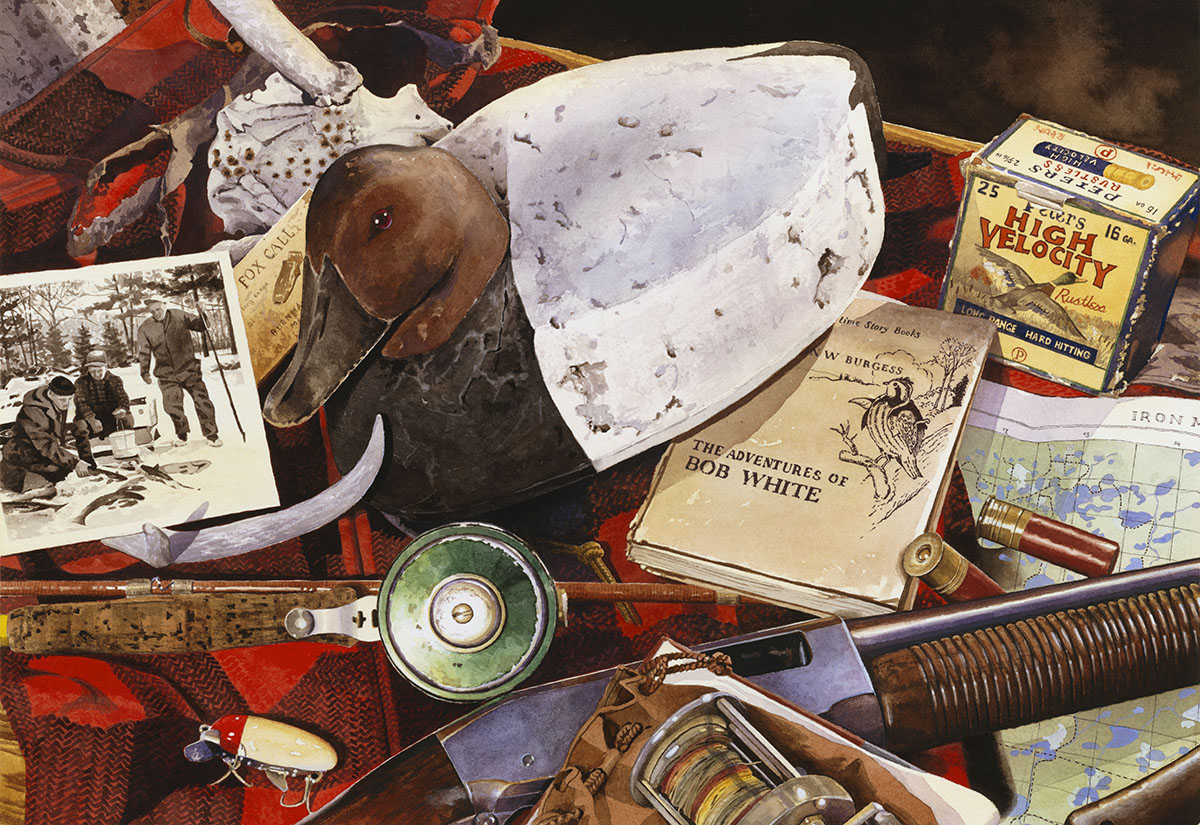

The studio where I paint and write is full of things I’ve collected over the years. The shelves are lined with rows of hand carved decoys, old books, antique fly reels, and countless relics. The windowsills are overrun with bird and game calls. The walls are covered with photographs of bird dogs, mentors, family, and friends, most of them holding a fly rod or shotgun. There’s a ‘Blazo’ box from Alaska in the corner; it’s full of bamboo rods, landing nets, snowshoes, old gaffs, and my son’s .22 rifle.

Behind the woodstove is a beer crate of rocks and other relics… at least one from every river I’ve fished. I believe that the spirit of these rivers, and the fish that live there, are alive in the rocks; that they need only to be placed in water to tell their ancient tales.

On my desk is a big glass cookie jar, the kind you might see on the counter of an old general store. Lisa calls it my “Boo Radley Jar” because it’s filled with the little treasures that no one but a child or an innocent would think to keep.

There are pocketknives and bass plugs, dog collars with bells, an old baseball, harmonicas, bootlaces, and buttons from many a retired canvas shirt. The bottom of the jar is layered with coins from far off places where I’ve knocked around, a few grouse feathers, and much more.

It’s full of memories.

Some people would consider my world cluttered, but I don’t feel encumbered. It’s a warm and welcome feeling to be surrounded by my past. Particularly so, when I consider that the most important of these objects found me.

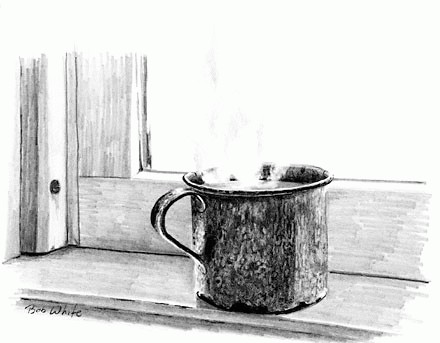

It seems that everything around me has a story to tell. The rusty tin cup on my desk, for example, found me at my first river camp in Alaska.

The camp was inherited from another guide in midseason. As I unloaded my gear from the Beaver that evening, and set it on the gravel bar, the guide who I was to replace seemed much too anxious to leave. His duffels and other kit were tossed through the open doors as if they were weightless.

“You’ve got lots of slugs and ‘buck, right?” he asked, offering me two hands full of shells. “I won’t be needing these back at the lodge. You better take ‘em.”

“Sure,” I said, as he thrust them at me. Most of them spilled into the shallow water at my feet.

“Thanks, Toby… Uh?”

“Yeah?”

“You don’t have, ah… bear problems, do you?”

“Nothin’ you can’t handle now,” he said as he bounded through the open door and onto his pile of gear. “Gotta go… see ya!”

“Clear!” The Boss called over his shoulder.

“Clear!” Came the expected reply.

The Boss taxied down river, around the broad sweeping bend, and went out of sight. I heard him do his run up and seconds later he reappeared on step, holding one float on the water as he took the corner. Toby’s face was pressed to the window. He looked relieved.

The first thing a guide does when he inherits a river camp is to take stock, and make it his own. For me, this meant a brief inventory, and then a cleaning. I hadn’t gone far into the process before I realized that I was in trouble, that some interesting nights lay ahead. There was a trail of trash a few yards behind the tent that had been spread out and drug into the woods by at least three bears.

That’s just great, I thought to myself.

I went down to the river to look over the boats and take stock of what I had for gas and two-cycle oil. The boats and everything around them had also been trashed. The seat cushions and life jackets were in shreds, gas cans were tipped over and leaking, and the Clorox bleach bottles of two-cycle lay on their sides oozing syrupy red oil from multiple holes.

“Wonderful.” I said under my breath.

There was bear spoor all around the place, and as I suspected, there were two sets of little tracks to go with the big ones. I’d waded into the river to retrieve one of the oars that had been gnawed when I realized that some of the tracks in the mud hadn’t yet filled in with water. The hair on the back of my neck started to rise, and I slowly turned around. There, in camp, between the tent and the cooking fly, and more importantly, between my shotgun and me, were my three new friends.

“Goddamnit.” I said aloud.

The sow stood to her full height and squinted as she looked for trouble. Now, one of the first things you learn about bears when you show up at an Alaskan fishing lodge is that you should never, ever run from them. It’s supposed to trigger their predatory instincts, and most importantly… it’s a race you can’t win. The cubs were out of sight behind the tent, but momma felt threatened and started down the bank, convinced that I was the trouble.

“Shhhit!” I screamed, as leapt into one of the boats. I jumped on the seat to grab the oars, but only found one. I stumbled into the back of the boat hoping to get the ancient outboard started, only to find that the running can had been ripped from it’s hose and was nowhere in sight. I grabbed the only oar and using it as a pole, pushed my way out into the current and safety.

As I floated down the river, spinning in circles, I wondered how far I’d drift before hitting a bank… and how the hell I’d get back to camp with no motor and only one oar.

When I finally made it back, the camp was utterly destroyed. I tidied up as best as I could, and crawled into my sleeping bag with the knowledge that it would take a major house cleaning to change the bears’ dining habits.

I didn’t sleep well that night. I was new to Alaska and unnerved not to be at the top of the food chain. I awoke every few minutes wondering if I’d heard bears, or just imagined it.

I was finally asleep when the plane buzzed over the next morning to bring me fishermen. I must have looked as bad as I felt because uncharacteristically, The Boss took a moment to ask, “Are you okay?”

I made it through the day, reluctantly said goodbye to my fishermen and stumbled back to camp. As tired as I was, I knew the only solution I had, short of moving, was to start cleaning. I dug a pit as deep as I could, fifty yards away, and hauled every scrap of trash I could find to it. When it has half full, I poured on a liberal amount of avgas and touched it off. As bad as it smelled, it was a comfort to have a big fire and I decided to build one at camp as well. The campfire eased my fear, until I heard the bears down on the beach trashing the boats again. I loaded the shotgun with as many shells as I could, and lay down on top of my sleeping bag, afraid to zip myself in and not be able to get to it. Thus began my slow decent into sleep-deprivation-hell.

Over the next week I doubt that I slept for more than a few minutes at any one time. I began to have nightmares of bears coming through the tent at me. These hallucinations became so real that I had to count my shells every morning… and I still remember the number. I cleaned the camp area with a fervor that would have made my Germanic ancestors proud; I sterilized the place. I began to cook on the gravel bar. In the evening I took every scrap of food in camp and placed it into one of the boats with everything that wasn’t nailed down, and anchored it out in the middle of the river.

The only thing in camp besides my clothes, sleeping bag, shotgun and the escape boat was, me.

And, still they came, which in my troubled state of mind really messed me up. Then, when I was about at the end of my rope, I was told that the head guide, Rusty, would stop by and spend the night while he ferried a couple of boats from the Lower Nush, to Nuyakuk Falls.

Rusty arrived late in the evening. He had long flaming red hair and a full beard to match. His trip had taken him all day and he wore ski goggles and thick orange, rubberized gloves that came up to his elbows. His hair was wild and wind blown, and when he took off the goggles, had the look of a ferocious hedgehog. I was never happier to see someone… anyone, nor more grateful for the company.

After dinner, he produced a bottle of whisky from his bag and we shared some from an old tin cup that I had found hanging in a spruce tree next to the tent. Rusty eyed the cup with a bit of nostalgic familiarity, and his eyes clouded over as he took the last sip, and then hung it back on the rusting nail where I’d found it weeks before.

After dinner, he produced a bottle of whisky from his bag and we shared some from an old tin cup that I had found hanging in a spruce tree next to the tent. Rusty eyed the cup with a bit of nostalgic familiarity, and his eyes clouded over as he took the last sip, and then hung it back on the rusting nail where I’d found it weeks before.

“Well, I’d better

clean up.” I said, and began my nightly ritual of hauling all of the food down to the boats.

Rusty watched in quiet fascination, while slowly rolling a cigarette. After he’d smoked it, he asked, “Just what in the hell are you doing?”

“Well, Rusty, you see, I… we’ve got bear problems.”

“I see that,” he replied. “So why in the hell are you putting all of your food out in a boat where they can git it?”

“Well, I…”

“Do you want to lose it? Git all of that food back up here and put it in the tent!”

At this point, I really didn’t care about the food. If I lived through the night and got a few minutes of sleep doing so, I’d be happy enough.

Later, Rusty rolled his sleeping bag out in the tent so that the food was between us, arranged his shotgun on the ground by his side, and slid a clip into a 9mm automatic, which he laid on his chest.

“Sweet dreams.” I heard him say as I drifted off to sleep.

—

Postscript: Although the bears frequently came back, I survived the summer. In the fall when I left, I took that old tin cup with me. It hangs on a peg in the kitchen.

Not running from a bear is easy advice to give… but a really hard thing not to do.

As of this writing, “Rusty” still guides in Alaska.