Each day provides its own gifts – American Proverb

During my first season in Alaska all the guides gathered around a bonfire each night to unwind, review the day, and listen to Rusty. The old guide was the consummate bush rat, and had forgotten more about living and working in Alaska than many of us would ever learn. His flaming red hair stuck out from under his hat at odd angles, and he had a wild beard to match. Like a good parent, Rusty encouraged us when we did well, admonished us when we needed it, and, tried to pass along some of life’s important lessons. “Fish are the world’s best barometers of karma,” he cackled, and then pushed another spruce round into the dying fire. Sparks towered into the soft Alaskan dusk.

We all leaned in and waited for him to continue. Rusty took a sip of whiskey from an old tin cup, smacked his lips, and then closed his eyes. Seconds later he opened them, as if he’d never said a thing, and watched the sparks trail off down-wind toward the coast. I couldn’t stand the suspense. “What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well,” he said, slowly placing the tin cup on the log next to me, “I had two guys in my boat today that couldn’t have been more different. One was a real nice guy. If he wasn’t sure about something, he asked, and more importantly, he’d listen. If something needed doing, he offered to help; that sort of guy.”

“Yeah?”

“The other sport was a real pain-in-the-ass; he knew something about everything. He knew where every fish in the river ought to be, and wasn’t bashful about saying so. He knew what side of the river we should drift, and then instructed me on how to hold the boat. Hell, he even knew what flies to use.”

“Yeah?”

“Well, the good guy had tied a bunch of flies ‘specially for the trip. They weren’t much to look at, but I could tell that he was real proud of them. He had faith in ’em, you know? Sort o’ like a kid believes in Santa Claus.”

“And?”

“The sport laughed at them; told him there was no Santa. He even refused to take one, jest in case they’d worked.”

“Jeeze, that’s low,” someone said from across the blaze. “What happened?”

“Waugh!” Rusty laughed. “I reckon the price of those flies has tripled. The expert couldn’t buy a fish all day, and the other guy just caught the hell out ’em! ”

Rusty took another sip of whiskey and waited for the laughter to die before leaning in conspiratorially, as if he had a secret to tell us. We gathered even closer to listen. “If fish judge our karma,” Rusty said in a whisper, his face aglow from the dancing flames. “Then, the flies we throw at them are windows to our souls.”

The younger guides looked at each other in confusion, but Rusty met my gaze and held it. He had somehow come to understand my obsession with flies. He smiled, winked, and finished his whiskey.

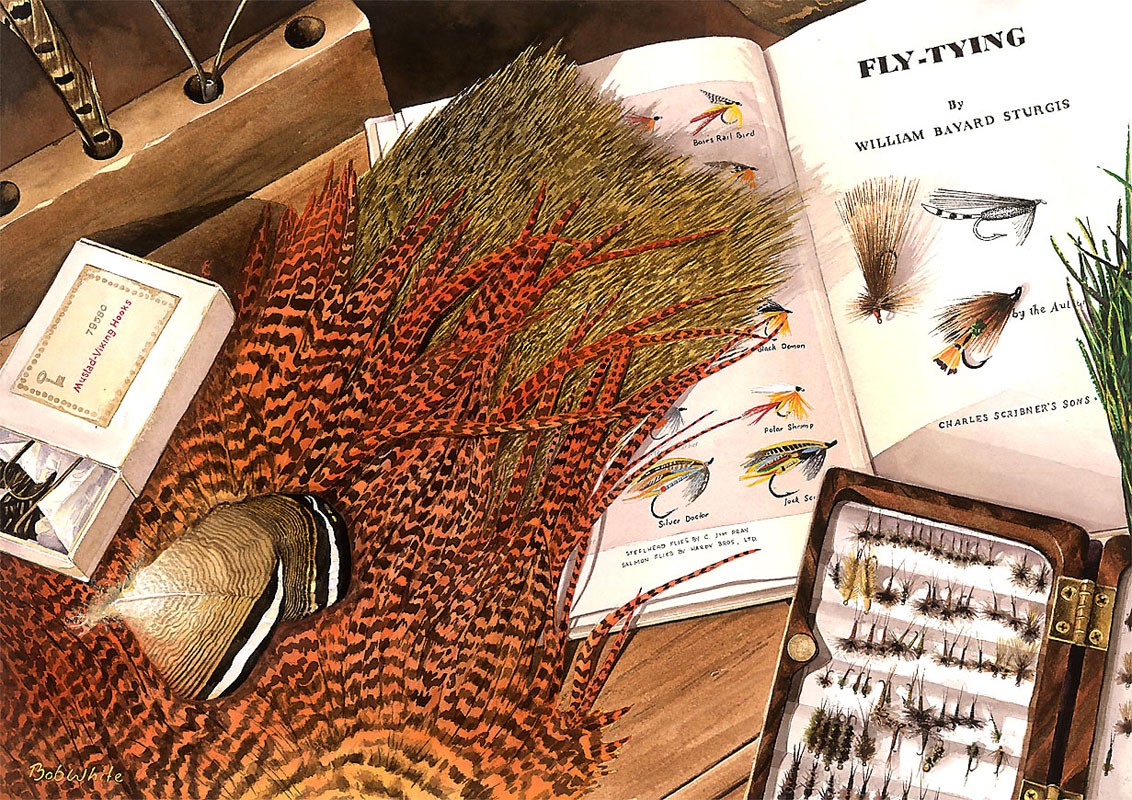

My love for flies began the day I discovered an old, yellowed box of them in the dark recesses of our attic. When I asked my father about the flies, he told me that he’d tied them as a boy. From that day forward, I considered flies a trick of alchemy, and anyone who tied them a wizard.

I was given a fly tying kit for my tenth birthday, and I added to the colorful materials with what money I earned mowing neighborhood lawns. I had thousands of trout flies tied long before I ever wet my feet in a stream.

I collect flies and tying materials like some people collect stamps, and clearly recall many of the early flies I created. One, in particular, was tied when I was thirteen-years-old. It was a standard Adams, but constructed with a long, stiff tail of moose mane. At the time, I wasn’t very good at tying dry flies, but the proportions of this particular fly were perfect; it was a complete accident, or perhaps even divine intervention. I’ve tried in vain to copy it and replicate the miracle, but I’ll never again tie a fly so perfect.

For years, I kept it safely sequestered in a special compartment of my fly box, I wouldn’t dare risk it to a snag, or have it damaged by a fish. It became clear to me at an early age that the flies I tied and collected were often more important to me than the fish I sought to catch with them.

I was twenty years old, and fishing with a mentor, when I came upon a fish worthy of this particular fly. The 18-inch brown rose to the second drift, took the fly, and I landed it as my friend walked up behind me to watch. The trout was admired and released, and the fly went back into the box, where it is today, a slightly worn treasure.

Over our years in Alaska, Lisa and I have worked with a lot of fine people who remain good friends to this day. A few weeks before Christmas, as I struggled with what to send the three boys of our closest friends, it occurred to me that I rarely have the opportunity to tie flies anymore. There are boxes upon boxes of materials and tools that will never be used if left to my care. In a moment of clarity, I decided to send the boys everything they’d need to tie their own flies. The day was spent rummaging through my materials, selecting boxes of hooks, assembling the necessary tools, and noting how they might be used.

Sorting through those boxes was a powerfully nostalgic experience. Few casual fly tyers ever deplete a piece of material, and I’d collected hundreds of remnants. Those half-used hackle necks, patches of deer hide, and countless spools of floss and tinsel, transported me back in time, and I found myself surrounded by my fly fishing past.

The package I took to the post office the next morning contained more than just bags of feathers, bits of fur, hooks, and spools of shiny tinsel. What was delivered to a cabin in Alaska on Christmas morning were the necessary ingredients for creating tiny and precious bits of hope.

I believe that every fly is a little seed of hope, the dream of a fish yet to be hooked and played on a distant and unknown river. I also believe that hope runs deeper when it’s created late in the night, at a fly tying bench, while remembering time spent on the water, in anticipation of another day.

Two days after sending the fly tying materials to my three young friends in Alaska, I received conformation of karmic balance. A package arrived from Canada. It had been sent to me at the bequest of an old friend. Inside the box, carefully and lovingly wrapped, was a fly reservoir from the turn of the century. The large box was painted with black lacquer and its lid marked, Salmon Flies. The interior of the box was lacquered in cream, and the inside lid stamped, A. Carter & Co., 11 South Moulton St., London. Nested within were nine tidy trays, each one overflowing with fully-dressed salmon flies, streamers, wet flies and dries – a life’s collection of hopes and dreams, all windows to one man’s soul.