The most potent muse of all is our own inner child. — Stephen Nachmanovitch

The restlessness in the air was palpable, as I stared blankly at the unfinished canvas. The palette was mixed and my brushes ready, but nothing stirred. It seemed as though my muse had abandoned me to walk the late summer fields alone. Perhaps I should do the same, I thought, smiling at the notion that we might run into each along the way.

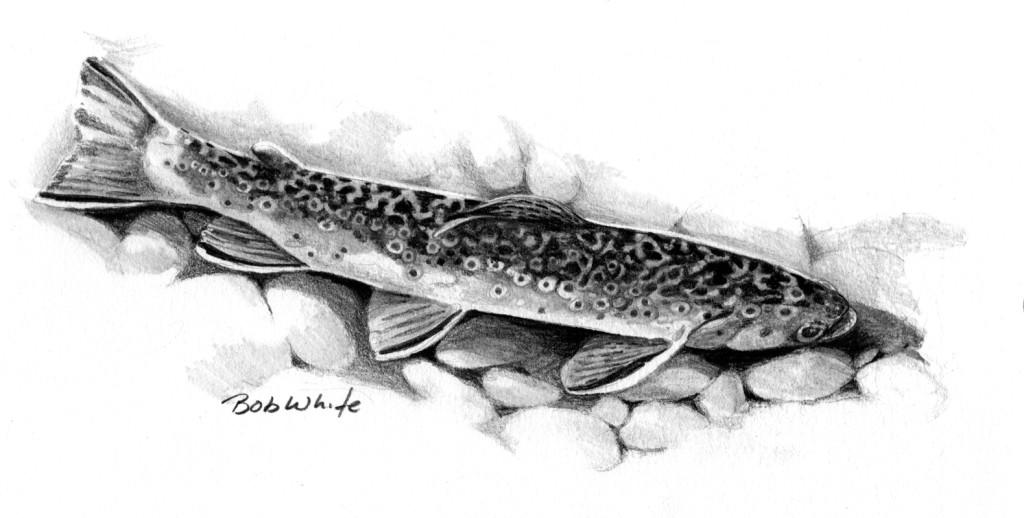

Having decided on a walk, I collected a pail to hold watercress and my four year-old-daughter to help gather it from a small stream born on the hillside above the little town where we live. Along the way, we crossed the old Mill Stream, and stopped to look at the brook trout living in the protective shadow of the little stone bridge that spans it.

Tommy knows the ritual well: She was on her toes and I was on my knees as we slowly poked our noses over the wall to peer into the shaded pool. At first there was only the reflection of sky, and then the top of her head, and finally her blue eyes straining to see into the darkness. The trick, which she will undoubtedly learn in time, is to look through the reflection and focus on the bottom, where the little trout hold themselves finning in the current.

These brookies, already mature at five or six inches, were in their spawning colors. Their bellies glowed a deep pumpkin orange, their fins were as red as autumn sumac, and the ivory edges seemed even brighter by comparison. “Do you see them?” I asked, switching my focus back and forth between the reflection of her searching eyes and the fish.

“Sure,” she said, edging even higher, but the truth was revealed when her eyes widened at the sudden swirls of sand where the fish had been. As I watched the sand drift away in the current, it occurred to me that, like my muse, I too become restless in late summer and feel drawn to wander.

I shortened my stride as we walked hand-in-hand up the hill, out of town, and my thoughts slowed to match our pace. I stopped thinking about my painting and watched the grasshoppers flush from our path. Tommy broke my tentative grasp to chase after them, and the clacking of their wings stopped only after they’d caught enough of the light breeze to sail off to safety. Cicadas buzzed in an unseen chorus, hidden in trees whose leaves, lit by the late afternoon sun, glowed like an animated stained-glass window. In a sudden gust of wind, maple seeds twirled past, and Tommy giggled and danced among them, twisting like one of the many pods that enveloped us. With seeds caught in her hair, she looked like a Wiccan goddess celebrating the fullness of the season.

The landscape was swollen and ripe, with long ultramarine shadows falling across rolling ochre fields toward distant and hazy cobalt hills. I felt as compelled to paint it as I am compelled to ask a pregnant woman when her baby is due.

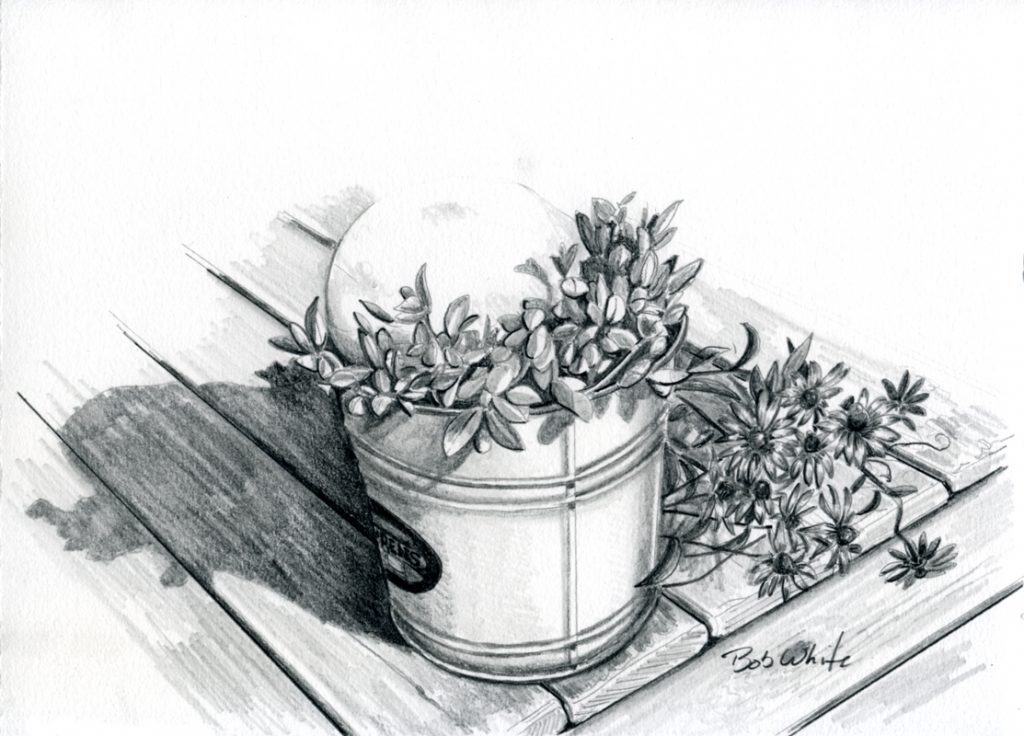

Tommy ran ahead through the lemon-colored grass, but stopped to wonder at a wildflower covered in painted ladies. As we marveled at the little red and black butterflies, I set down the pail, and in doing so spied an unexpected prize. I called to Tommy, intending for her to find the giant mushroom—a perfect ivory puffball—but I was too excited, and pulled it from the loam to show her. It smelled simple and clean, like the earth from which it came. It was too large to fit in our bucket, so I set it in the shade to be retrieved upon our return, though Tommy was reluctant to leave her treasure for fear someone else might wander by and claim it.

Our path led us to the brook, where it tumbles through a series of steep tight corners. At certain times of day, especially in the evening, it sounds uncannily like a dialog between two small river gnomes, one with a low, hollow voice who speaks steadily and patiently, as a parent to a child. The other voice is high and animated, trying to speak over the first, like an insistent child. “Do you hear that?” I asked Tommy, stopping in my tracks for emphasis.

“Who is it?” She asked, an edge of fear creeping into her voice.

Her worry put an end to my playful deception, and I explained that the brook sometimes sounds like people talking. “Come on, squirt; let’s sit on the little bridge, put our feet in the water, and listen to what they have to say.” Tommy liked the notion of being invited to do something usually forbidden by parents: getting wet.

We gathered a bucket of cress for dinner, then a bouquet of wildflowers for Tommy’s mother, and finally we stopped in the woods to fetch our mushroom. The lingering afternoon had turned to evening, and the grasshoppers we flushed on the way home were slower in the cooling dusk. They flew only a few yards before landing, and would normally have been easy pickings for Tommy, except that she too had grown tired with the passing of the day.

Tommy brightened when she saw her mother in the kitchen window, and rushed in the house to show her the treasures we’d gathered. From the backyard, I watched my little woodland fairy and her mother in the soft glow of the kitchen as they washed the cress, admired the mushroom, and relived the afternoon.

I turned back toward the studio with a sigh, but stopped when I heard the soft plaintive dialogue of geese working their way down the St. Croix valley to the safety of their roost. I watched them against the lowering sky for as long as I could, reluctant to turn away even after they were out of sight, such is the primal magic in their calls.

When their song finally faded into the night, I walked to the shed for the season’s first armload of firewood. “It’s gotten cold,” my muse said from the darkness. “The season has changed.”

A version of this essay was first published in the September – October 2009 issue of Gray’s Sporting Journal.