The morning was cold and clear, but it held no joy. The decision was made: this would be our last summer in Alaska. As the season rushed toward its end, each day brought a long list of farewells, and as I turned inward to say goodbye, I etched even the smallest details into my memory.

“The last day,” Lisa said as I laced my high boots. “I’m glad you two guys will spend it together.”

“Do you think he knows?” I looked down at our Gordon setter.

“All Mac cares about is finding birds,” she said, and Mac’s tail began to thump the cabin floor.

“You’re right,” I said, and scratched his ears.

As Gordon setters go, Mac was small and moved like a cat, with a smooth, low gait that was deceptively fast. Although small in stature, he was made to hunt big, and there’s no bigger cover than where we were headed for the day. The high, windswept treeless tundra suited us both: Mac could run freely, and I could usually see him, though he might be only a tiny dot on a distant ridgeline.

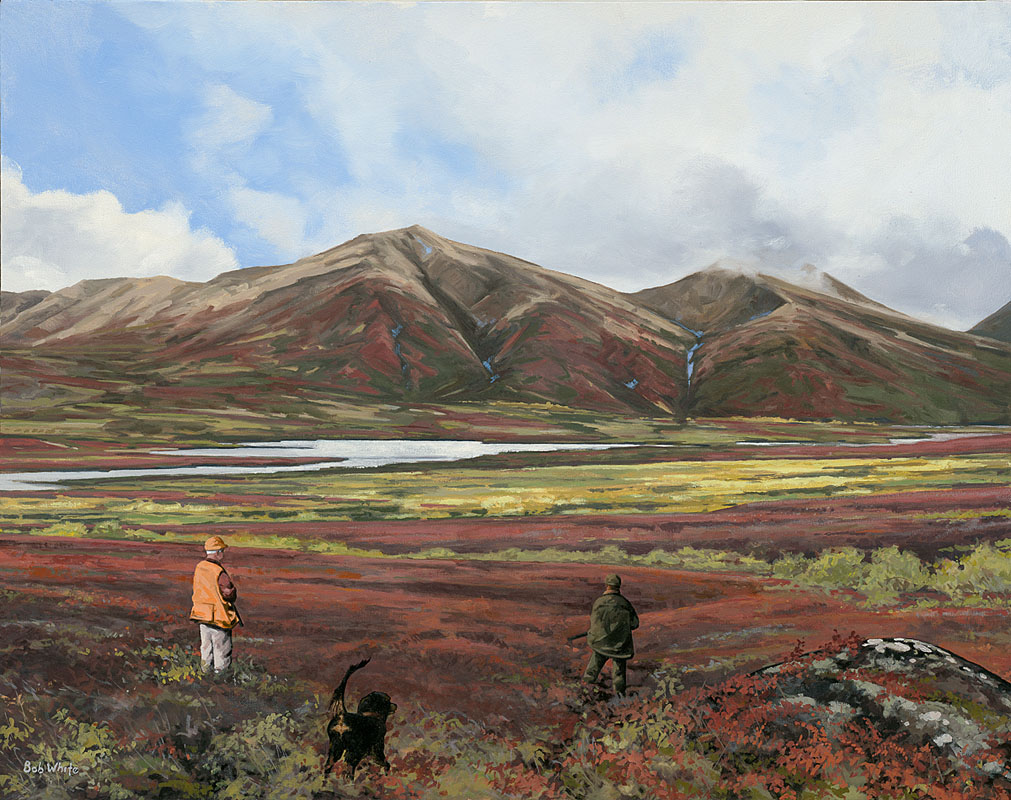

Because it would be our last ptarmigan hunt together, I planned to visit my favorite cover: the rolling hills on either side of a high mountain lake, cradled in a valley between two ranges of peaks. There would be no fences to cross or permission to ask. The day was ours, and we’d hunt with the wind in our faces and the low autumn sun at our backs. If we found birds, we might hunt the other side of the lake after lunch, or we might begin to work our way back to the lodge and drop in on some other cover along the way.

Mac fell asleep in my lap as the old floatplane worked its way west over the Kilbuck Mountains. Normally I’d have joined him for a nap, but I wanted to take in as much as I could of the world stretched out below. As if sensing my need, or perhaps because of needs of his own, the pilot took the long route. Long shadows of ultramarine jumped from the jagged peaks near the pass we sought and then marched away, retreating as the sun climbed higher.

Once over the divide, we followed a thread of glacial melt until, joined by others, it became a stream that flowed into a river that became the lake. Long and fiord-like, the lake seemed ridiculously blue, and we followed its shoreline until it ended and another river began, then another lake, and eventually a distant river that meandered through golden cottonwoods as it flowed to the Bering Sea.

Somewhere along the way, we left the valley and its dream. The tundra below was a riot of color, and we followed a tributary high into the hills where we would hunt.

Mac was awake now, shivering as we taxied toward the gravel point where we’d beach the plane. There’d be no keeping him close while we unloaded—an accommodation we’d arrived at over time. Mac sensed when my hunters were ready for business, and he appeared at my side before I could whistle.

“We’ll work toward that distant ridge,” I began, “but Mac’s in charge. If he gets birdy, we’ll follow his lead.” This was another lesson I’d learned from Mac: the birds are where the dog finds them, and he’s the one with the nose. There’s no point in arriving at a planned destination without finding birds.

Halfway to the ridge, Mac ran into birds; they flushed wildly, far out of gun range. As was his habit, he followed. The birds seemed to be laughing at him, and while I could sympathize with his need to exact justice, busting birds out of gun-range was one accommodation I couldn’t make.

I stormed ahead of the hunters, hoping to catch my setter for a private word or two. When I crested the rise, I expected to see him running across the next ridge in hot pursuit. Instead, he was locked up on point—but not the kind of point I’d expect from a dog that comes into birds at high speed. He wasn’t pointing at the ground in front of him, or corkscrewed around, pointing at a bird he’d passed. His head was high, his eyes focused on something distant. He turned his head slightly and rolled his eyes just as the first of the hunters hustled up behind me.

“Geeze, would you look at that.” I followed the hunter’s pointed finger across the draw to the distant ridge, where dozens of white heads watched our every move. As the other hunters joined us, hundreds of ptarmigan raised their heads to stare.

Mac stood staunchly as my hunters spread out and walked toward the hillside, but in only a few steps the entire slope erupted. Nobody fired a shot as the flock flushed as one, wheeled together, and flew down the valley. Mac didn’t follow.

Later in the day, Mac flawlessly pointed several birds, all cleanly killed and artfully retrieved, the memories of which I’ll always carry.

Someday I might once again walk the high autumn tundra and thrill to the flush of ptarmigan, but it will be without my little Gordon setter. Mac rests in the back yard now, his grave pointed north, to the cover and the birds he loved.

This illustrated essay was published in the August 2011 issue of Gray’s Sporting Journal.